The McDonald’s on the corner of Third Avenue and 58th Street in New York City doesn’t look all that different from any of the fast-food chain’s other locations across the country. Inside, however, hungry patrons are welcomed not by a cashier waiting to take their order, but by a “Create Your Taste” kiosk – an automated touch-screen system that allows customers to create their own burgers without interacting with another human being.

It’s impossible to say exactly how many jobs have been lost by the deployment of the automated kiosks – McDonald’s has been predictably reluctant to release numbers – but such innovations will be an increasingly familiar sight in Trump’s America.

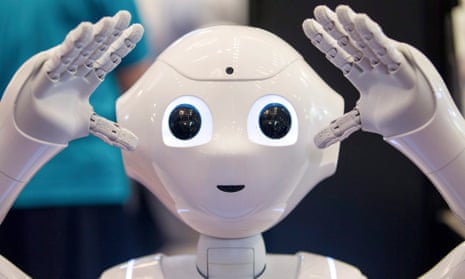

Once confined to the pages of futuristic dystopian fictions, the field of robotics promises to be the most profoundly disruptive technological shift since the industrial revolution. While robots have been utilized in several industries, including the automotive and manufacturing sectors, for decades, experts now predict that a tipping point in robotic deployments is imminent – and that much of the developed world simply isn’t prepared for such a radical transition.

Many of us recognize robotic automation as an inevitably disruptive force. However, in a classic example of optimism bias, while approximately two-thirds of Americans believe that robots will inevitably perform most of the work currently done by human beings during the next 50 years, about 80% also believe their current jobs will either “definitely” or “probably” exist in their current form within the same timeframe.

Somehow, we believe our livelihoods will be safe. They’re not: every commercial sector will be affected by robotic automation in the next several years.

For example, Australian company Fastbrick Robotics has developed a robot, the Hadrian X, that can lay 1,000 standard bricks in one hour – a task that would take two human bricklayers the better part of a day or longer to complete.

In 2015, San Francisco-based startup Simbe Robotics unveiled Tally, a robot the company describes as “the world’s first fully autonomous shelf auditing and analytics solution” that roams supermarket aisles alongside human shoppers during regular business hours and ensures that goods are adequately stocked, placed and priced.

Swedish agricultural equipment manufacturer DeLaval International recently announced that its new cow-milking robots will be deployed at a small family-owned dairy farm in Westphalia, Michigan, at some point later this year. The system allows cows to come and be milked on their own, when they please.

Data from the Robotics Industries Association (RIA), one of the largest robotic automation advocacy organizations in North America, reveals just how prevalent robots are likely to be in the workplace of tomorrow. During the first half of 2016 alone, North American robotics technology vendors sold 14,583 robots worth $817m to companies around the world. The RIA further estimates that more than 265,000 robots are currently deployed at factories across the country, placing the US third worldwide in terms of robotics deployments behind only China and Japan.

In a recent report, the World Economic Forum predicted that robotic automation will result in the net loss of more than 5m jobs across 15 developed nations by 2020, a conservative estimate. Another study, conducted by the International Labor Organization, states that as many as 137m workers across Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam – approximately 56% of the total workforce of those countries – are at risk of displacement by robots, particularly workers in the garment manufacturing industry.

A Trump-sized problem

Advocates for robotic automation routinely point to the fact that, for the most part, robots cannot service or program themselves – yet. In theory, this will create new, high-skilled jobs for technicians, programmers and other newly essential roles.

However, for every job created by robotic automation, several more will be eliminated entirely. At scale, this disruption will have a devastating impact on our workforce.

Few people understand this tension better than Dr Jing Bing Zhang, one of the world’s leading experts on the commercial applications of robotics technology. As research director for global marketing intelligence firm IDC, Zhang studies how commercial robotics is likely to shape tomorrow’s workforce.

IDC’s FutureScape: Worldwide Robotics 2017 Predictions report, authored by Zhang and his team, reveals the extent of the coming shift that will jeopardize the livelihoods of millions of people.

By 2018, the reports says, almost one-third of robotic deployments will be smarter, more efficient robots capable of collaborating with other robots and working safely alongside humans. By 2019, 30% or more of the world’s leading companies will employ a chief robotics officer, and several governments around the world will have drafted or implemented specific legislation surrounding robots and safety, security and privacy. By 2020, average salaries in the robotics sector will increase by at least 60% – yet more than one-third of the available jobs in robotics will remain vacant due to shortages of skilled workers.

“Automation and robotics will definitely impact lower-skilled people, which is unfortunate,” Zhang told me via phone from his office in Singapore. “I think the only way for them to move up or adapt to this change is not to hope that the government will protect their jobs from technology, but look for ways to retrain themselves. No one can expect to do the same thing for life. That’s just not the case any more.”

Meanwhile, developments in motion control, sensor technologies, and artificial intelligence will inevitably give rise to an entirely new class of robots aimed primarily at consumer markets – robots the likes of which we have never seen before. Upright, bipedal robots that live alongside us in our homes; robots that interact with us in increasingly sophisticated ways – in short, robots that were once the sole province of the realms of science fiction.

This, according to Zhang, represents an unparalleled opportunity for companies positioned to take advantage of this shift, yet it also poses significant challenges, such as the necessity of new regulatory frameworks to ensure our safety and privacy – precisely the kind of essential regulation that Trump spoke out against so vociferously on the campaign trail.

According to Zhang, the field of robotics actually favors what Trump pledged to do on the campaign trail – bring manufacturing back to the US. Unfortunately for Trump, robots won’t help him keep another of his grandiose promises, namely creating new jobs for lower-skilled workers. The only way corporations can mitigate against increasing labor costs in the US without compromising on profit margins is to automate low-skilled jobs.

In other words, we can bring manufacturing back to the US or create new jobs, but not both.

Time for a career change, then?

With millions of jobs at risk and a worldwide employment crisis looming, it is only logical that we should turn to education as a way to understand and prepare for the robotic workforce of tomorrow. In an increasingly unstable employment market, developed nations desperately need more science, technology, engineering and math – commonly abbreviated as Stem – graduates to remain competitive.

During the past eight years, science and technology took center stage both at the White House and in the public forum. Stem education was a cornerstone of Barack Obama’s administration, and he championed Stem education throughout his presidency.

On Obama’s watch, the US was on track to train 100,000 new Stem teachers by 2021. American universities began graduating 100,000 engineers every year for the first time in the nation’s history. High schools in 31 states introduced computer science classes as required courses.

Unfortunately, this progress is now in jeopardy.

Like many of his cabinet choices, President-elect Trump’s appointment of Betsy DeVos as secretary of education is darkly portentous. One of the country’s most vocal charter school cheerleaders, DeVos has little experience with public education beyond demonizing it as the product of governmental overreach.

DeVos and her husband Dick have spent millions of their vast personal fortune fighting against regulations to make charter schools more accountable, campaigned tirelessly to expand charter school voucher programs, and sought to strip teachers’ unions of their collective bargaining rights – including teachers’ right to strike. Despite these alarming shortcomings, Trump seems confident that a billionaire with little apparent interest in public education is the perfect choice for such a crucial role.

There is no doubt that this appointment will affect the opportunities of students keen to launch a career in Stem. Private schools such as Carnegie Mellon University, for example, may be able to offer state-of-the-art robotics laboratories to students, but the same cannot be said for community colleges and vocational schools that offer the kind of training programs that workers displaced by robots would be forced to rely upon.

In light of staggering student debt and an increasingly precarious job market, many young people are reconsidering their options. To most workers in their 40s and 50s, the idea of taking on tens of thousands of dollars of debt to attend a traditional four-year degree program at a private university is unthinkable.

Enter Silicon Valley: no need for a degree any more?

Solving inequality in tech has been a particularly challenging PR exercise for Silicon Valley. A report published by the Equal Opportunities Employment Commission in May 2016 found that just 8% of tech sector jobs were held by Hispanics, 7.4% by African Americans and 36% by women.

However, those numbers have done little harm to perceptions of Silicon Valley in general. Propelled by our enthusiastic consumer adoption of mobile devices, startup culture has become the latest embodiment of America’s Calvinistic work ethic. Graduates struggling to find jobs aren’t unemployed; they’re daring entrepreneurs and future captains of industry, boldly seizing their destinies by chasing bottomless venture capital financing.

“Hustle” has become the latest buzzword du jour, and it seems as though everybody is working on an app, trying to set up meetings with angel investors, or searching for a technical co-founder – including Daniel Hunter.

The son of two engineers, Daniel has been fascinated by robots his entire life. He spent much of his formative years building elaborate machines with Lego blocks, and later joined a robotics club near Sacramento, California. Before long, Daniel and his team-mates were pitting robots of their own design against those of other teams, and even won first prize in a regional robotics tournament.

Daniel is now preparing to complete his bachelor of science in robotics engineering at the University of California, Santa Cruz – one of a small but growing number of colleges across the US to offer a generalized undergraduate degree in robotics.

In addition to his studies in robotics, Daniel has also been improving his coding skills, in part to sate his intellectual curiosity, but also to further hone his competitive edge.

Daniel, who works at a startup that is currently developing an iOS app for sales professionals, is a firm believer in the new gold rush. He told me of his admiration for the work of libertarian journalist Henry Hazlitt, his ambitions to become a world-renowned roboticist and technologist (“I’m 21 now, so if by the time I’m 45 – Elon Musk’s age – I’ve established myself as a world-class mechatronics engineer, I’ll consider myself pretty successful”) and that he doesn’t believe everyone should go to college.

“I ask myself pretty regularly if the degree is actually worth it,” he says. “There’s a lot of side projects I could work on that might provide more value to my future than some of the classes I take, so it’s hard to justify.”

Daniel also told me that his experiences defy conventional wisdom that earning a college degree is the only pathway to success in today’s savagely competitive job market.

“I talk to as many employers and startup founders as I can, and I hear the same thing over and over: degrees mean less and less, experience is everything,” Daniel says. “In the age of Udacity, Udemy, MIT’s OpenCourseWare, it’s very possible to do a bunch of small personal projects, display that experience to an employer, and get hired.”

This appetite for alternatives to traditional higher education has driven intense interest in private programming schools and self-styled coding “boot camps” in recent years.

Intensive coding schools may be popular, but they have attracted more than their share of criticism – not least for their typically high tuition fees, low academic rigor, and vague promises of highly paid, full-time jobs upon completion.

On top of this, one of the most common arguments leveled against coding boot camps is that they do little to address the chronic underrepresentation of minorities and the exclusion of those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

“I think programming boot camps have been fairly criticized for the fact that there’s a lot of tension around the idea of economic mobility,” says Adam Enbar, a former venture capitalist and co-founder of Flatiron School, one of the most renowned private programming schools in New York City. “The reality is that most schools are fairly selective and very expensive, which means they tend not to be serving populations that really need a leg up economically; they’re really more often people who graduated with a good degree and want to change careers.”

Founded by Enbar and self-taught technologist Avi Flombaum in 2012, Flatiron School has implemented programs designed to make careers in technology more accessible to marginalized groups.

“For three years, we’ve been working with the city of New York on something called the New York City Web Development Fellowship, where we run programs exclusively focused on low-income and underrepresented students,” Enbar says. “We’ve done courses exclusively for kids from households with no degrees. We’ve done courses exclusively for foreign-born immigrants and refugees … When we enroll students at Flatiron School, we actually specifically look for people from different backgrounds. We don’t want four math majors sitting around a table together working on a project – we’d rather have a math major and a poet, a military veteran and a lawyer, because it’s more interesting.”

We don’t need any more food delivery apps – we need engineers

Developing a new iOS app may be more interesting than navigating the comparatively dreary worlds of logistics infrastructure, manufacturing protocols, and supply chain efficiencies, but America doesn’t need any more messaging or food delivery apps – it needs engineers. The question, according to Enbar, is not whether future engineers earn their degrees from traditional colleges or not, it’s about what a technology job actually is and how we, as a nation, view scientific and technical work.

In much the same way, many also believe we must examine the role of technology in primary education if we are to address growing concerns about labor shortages. Initiatives such as Hour of Code, a nationwide program that aims to highlight the importance of programming in K-12 education, have proven remarkably popular with educators and students alike.

According to Enbar, such initiatives are just one way America needs to examine its attitude toward Stem and traditional education. “I think the question we should be asking is ‘Why is this important?’” Enbar says. “We have to ask ourselves why we’re not mandating accounting or nursing or plenty of other jobs. The answer is that we’re not trying to create a nation of software engineers – it’s that this is becoming a fundamental skill that is necessary for any job you want to do in the future.”

Despite these grave threats, when I asked Daniel where he sees himself in five years, he remained cautiously optimistic.

“I’ll have my undergraduate degree and be several years into working,” Daniel says. “I don’t think I’ll go to grad school. I’m not sure if I’ll be working at a company or for myself – that largely depends on the opportunities I find once I graduate, and it’s pretty difficult to predict that.”

It is indeed difficult to predict how the gradual automation of the American workforce will take shape under Trump’s presidency. One certainty, however, is that the interests of those Americans at greatest risk of professional obsolescence will continue to be sacrificed in favor of serving, protecting and benefiting wealthy, white conservatives – a trend we are likely to see across virtually every aspect of life in Trump’s America and yet another betrayal of the predominantly working-class voters who believed Trump’s empty promises on the campaign trail.

As Enbar observed, the most urgent question we must answer is not one of robots’ role in the workforce of 21st-century America, but rather one of inclusion – and whether turning our backs on those who need our help the most is acceptable to us as a nation.

If history is any precedent, we already know the answer.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion