Inside the Supreme Court chamber of the U.S. Capitol on May 24, 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse sat down to make history. The moment was the culmination of more than 12 years of work, and it was only in the past year that Morse had finally convinced Congress to fund a $30,000 experimental project. After spending that past year snaking 40 miles of telegraph wire along a railway stretching from the nation’s capital to a train depot in Baltimore, Morse finally placed his hand on the telegraph key and tapped:

The question was an apt one because with that collection of dots and dashes, Morse had effectively opened the floodgates of the information age. Within a decade, 23,000 miles of telegraph wire criss-crossed the U.S., and in 1866—six years before Morse’s death—the first transatlantic wire connected America with Great Britain. Information that once took weeks or even months to reach its intended recipient, now took only seconds.

Over time, Morse’s invention lost technological relevance with the dawn of radio and telephones, but that special collection of dots and dashes (or “dits” and “dahs”) remained instrumental in military communications, especially during World War II and the Vietnam War. In fact, in 1966, naval commander Jeremiah Denton, then a prisoner of war of the North Vietnamese, delivered a secret message by blinking the word “TORTURE” in Morse code during an interview with a Japanese journalist.

But with the arrival of the internet, Morse code quickly receded from public life. The Federal Communications Commission dropped the requirement to learn Morse code for beginner amateur radio operators in 1991, the Coast Guard stopped using it 1995, and the requirement for ships at sea to scan for Morse code distress signals ended in 1999. By all accounts, Morse’s groundbreaking innovation was destined for the technological dustbin.

But, surprisingly, that didn’t happen.

Instead, Morse code became a small but vibrant part of the amateur (or ham) radio community. Hikers began taking small transceivers to the tops of mountain peaks to transmit dits and dahs, entire communities were established to preserve the art of Morse code, and even Google—the poster child of the modern information age—created tools to combine Morse code with machine learning to help give a voice to people with disabilities.

Here’s how Morse code works, the best method for learning (and crucially understanding) these dots and dashes, how to increase your words per minute (wpm) with easy-to-use apps, and recommendations for the best radio gear to get you started.

How Does Morse Code Work?

Samuel Morse is to the telegraph what Thomas Edison is to the light bulb—he didn’t necessarily invent the technology, but he did perfect it. Arguably, American inventor Joseph Henry should receive that accolade as he made fundamental discoveries that created stronger electromagnets, which allowed for electrical impulses to be transformed into mechanical work at a distance—which is basically the definition of a telegraph.

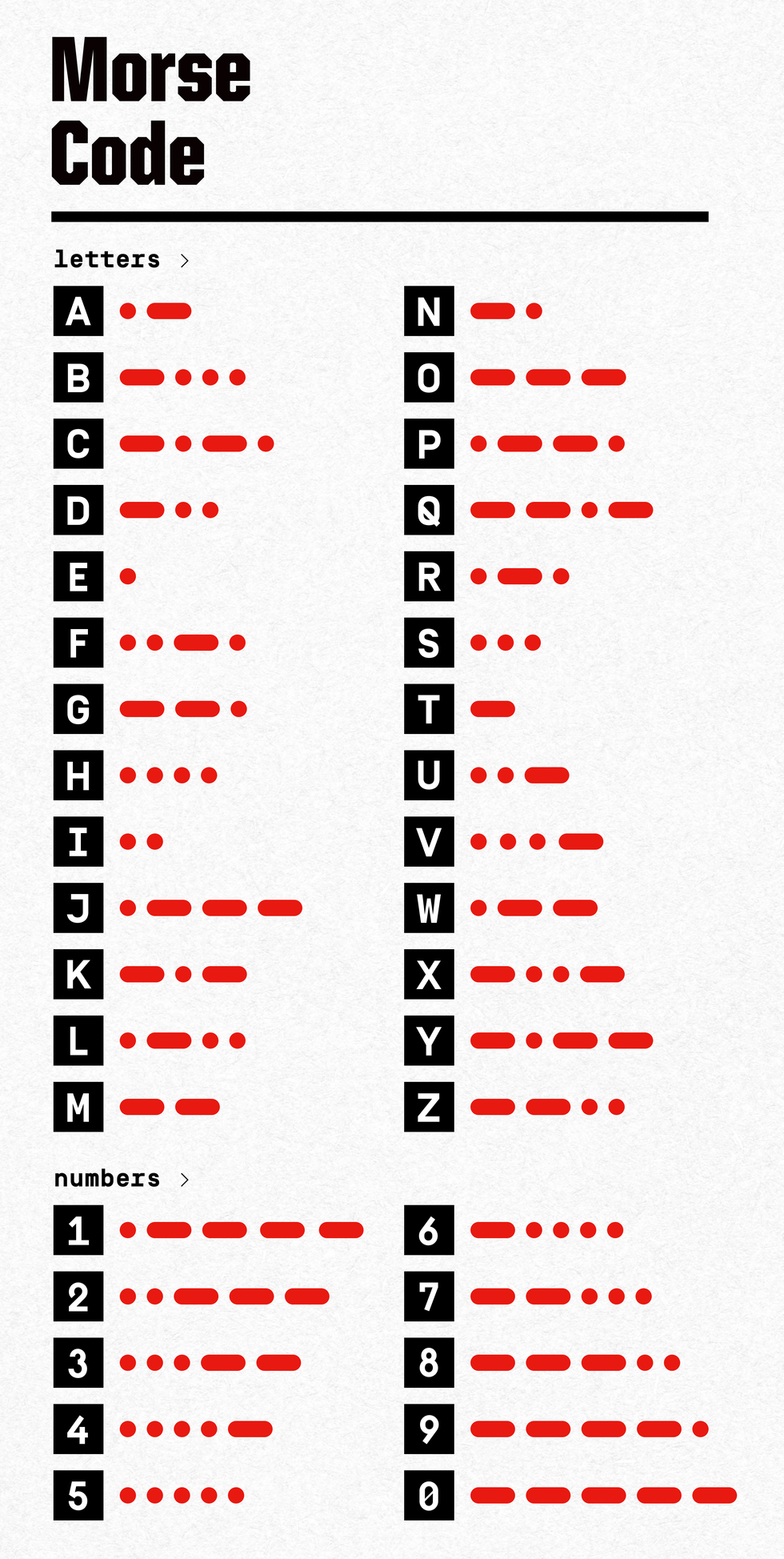

A telegraph key, the thing you tap with your fingers, creates an electromagnetic pulse that’s sent through a wire. A brief press of the telegraph key creates a dot, or “dit,” and a longer press creates a dash, or a “dah.” One of Morse’s key innovations was creating a simple system for how combinations of dits and dahs can make up 40 characters, including the 26 letters of the alphabet, numbers zero through nine, and four special characters.

This chart above shows the modern, international Morse code alphabet. (There have been a few changes in the past 180 years.) Morse created a code where less frequent letters were represented by a longer string of dits and dahs. So “T,” for example, is represented by only one dash, but “Z” is represented by two dashes followed by two dits.

To separate words and letters, CW (or continuous wave) operators use brief pauses, about three dots’ worth between letters and seven dots between words. So there you have it. Just memorize these 40 or so combinations of dits and dahs, learn the ebb and flow of pauses, and go have fun—right?

Yeah, it’s not that easy.

What’s the Best Way to Learn Morse Code?

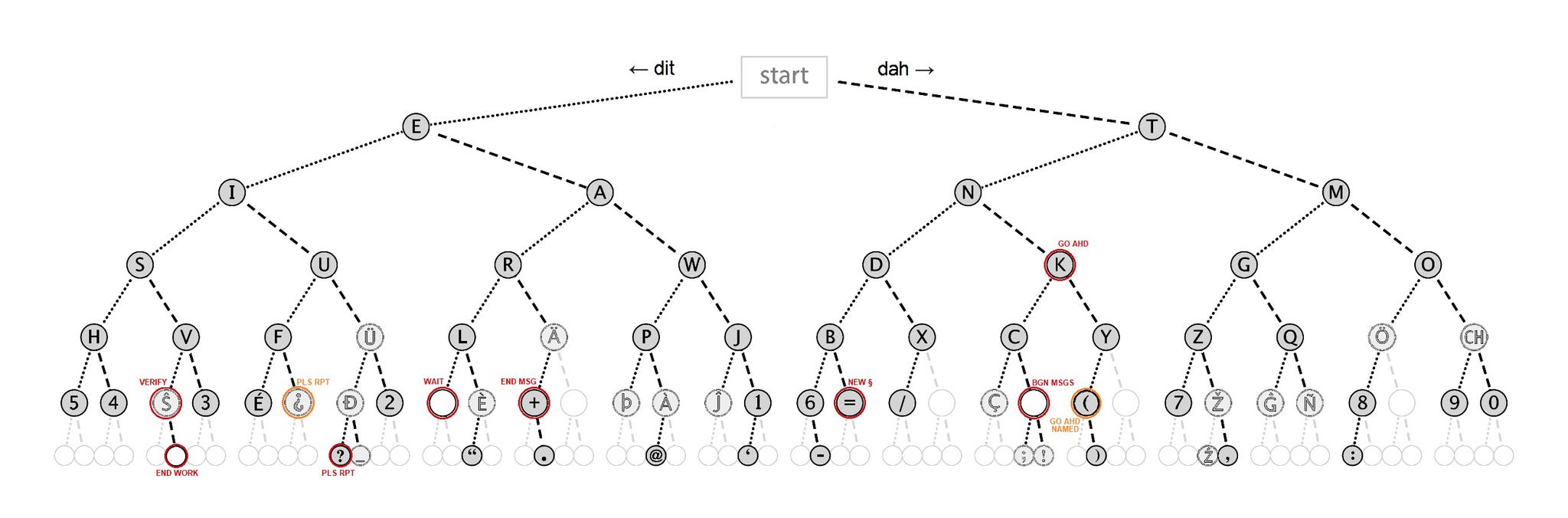

The decode chart shown above is a helpful way to visualize how the Morse code alphabet is put together, but that’s the problem—it “visualizes” it.

“Morse code is to our ears like color is to our eyes,” Glenn Norman, a Morse code instructor at CW Innovations, told Popular Mechanics. “You could never hear color, so you can’t see Morse code… to try to use your eyes to learn Morse code, it’d be like trying to learn colors with your ears.”

Norman first learned Morse code as an FCC requirement back in the 70s, but within the last decade rediscovered a passion for transmitting dits and dahs. Now retired after a long career in electrical engineering, Norman is an instructor teaching Instant Character Recognition (ICR) for Morse code operators looking to up their words per minute.

Many online tutorials will teach Morse code using this visual-based learning approach: a = 1 dit + 1 dah, b = 1 dah + 3 dits, etc. But an ICR approach puts the sounds first, so that Morse code operators learn to associate a certain pattern of sounds with a certain letter.

“When I say the letter ‘W’ you don’t hear the six different things I do with my vocal chords, my tongue, my lips, and my teeth... You just heard one sound,” Norman says. “Get the speed of the Morse code up so you hear the entire character as a single sound.”

Learning Morse code may seem simple at first, but laying those new neural pathways to associate a new collection of sounds with letters takes some time—but there are two bits of good news.

The first is that English is the default language of the international Morse code system (there is an American Morse code language that is mostly defunct), so that gives a leg up to native English speakers. And while learning Morse code takes commitment, it’s not the same as the years-long expedition to become fluent in a foreign language. But it’ll still take practice—about 30 minutes a day, six days a week, according to Norman.

“It’s not difficult, but you have to work at it. You have to put in the effort,” Norman says. “By a year, you’re probably at 10 words a minute. By two years, you’re at 20 words per minute or 25 words per minute. Most people stop there because that’s what people are doing on air—they’re talking at that speed.”

So what’s the best way to practice? Well, it sort of depends on your goals. If you’re really only wanting to decode Morse code and have no real interest in amateur radio, then you can go for the old method. In fact, Google designed a flashy tool—complete with handy mnemonic devices—to help people master the basics.

But most ham radio operators swear by the “Koch Method” for learning Morse code. Named after German broadcaster Ludwig Koch, the method begins with two letters (usually K and M) and only adds a new letter once the current letters are mastered. The difference between this method and other ways of learning is that the student sets the desired speed at which they want to learn from the beginning. So instead of starting at 5 words per minute and mentally checking off the dits and dahs in your head, the Koch method teaches you the entire sound of each letter rather than the components that make up those sounds—all at the speed at which operators communicate over the air.

“If someone wants to learn Morse code, the best way is to use the Koch method,” Norman says. “It’s going to introduce a single letter to you, and it’ll just drive home the sound of that letter.”

By taking this approach, you essentially skip learning Morse code twice—once to memorize the 40 combinations of dits and dahs and again to push past the plateau of 10 words per minute (which is about when your brain maxes out using the decode method).

The most popular free online trainer (for Windows) is G4FON, which has been offering a free Koch CW trainer app for decades, or you can learn for free in any web browser at Learn CW Online. But if you want to take training on the go, there’s also the Ham Morse iOS app and the IZUU2F Morse Koch CW app for Android. All of these programs teach Morse code using the Koch method. You can also try out Morse Code Ninja training courses, which go through each letter (similar to the Koch method) via a variety of YouTube videos.

If you really want to get serious about learning Morse code, there’s also a variety of online classes you can take, whether it’s CWops, Long Island CW Club, or Norman’s own advanced classes at CW Innovations.

How Do I Start Sending and Receiving Signals?

Another great way to train your Morse code skills is to, obviously, listen to some Morse code. Receiving is easy as all you need is a transceiver (more on that in a second), and you can start hearing Morse code over radio waves in no time. But if you want to eventually send signals, essentially becoming your own small broadcaster, then you need to go through a few extra steps.

The FCC regulates ham radio licenses and the 29 small frequency bands throughout the spectrum that are allocated for amateur radio enthusiasts. There are actually three types of licenses, so you can sort of choose your own adventure. Here’s how the the FCC describes each level:

- Technician: The privileges of a Technician Class operator license include operating an amateur station that may transmit on channels in any of the 17 frequency bands above 50 MHz with up to 1,500 watts of power.

- General: The General Class operator license authorizes privileges in all 29 amateur service bands.

- Amateur Extra: The privileges of an Amateur Extra Class operator license include additional spectrum in the HF bands.

Most amateur radio operators start with the Technician license, as it’s the easiest to acquire, and then advance from there. To practice for the test, head over to Ham Radio Prep to take a few of their sample tests. Strangely, taking this test requires no Morse code skills since sending dits and dahs is only a small subsection of the larger ham radio community, with other operators just sending via voice or data.

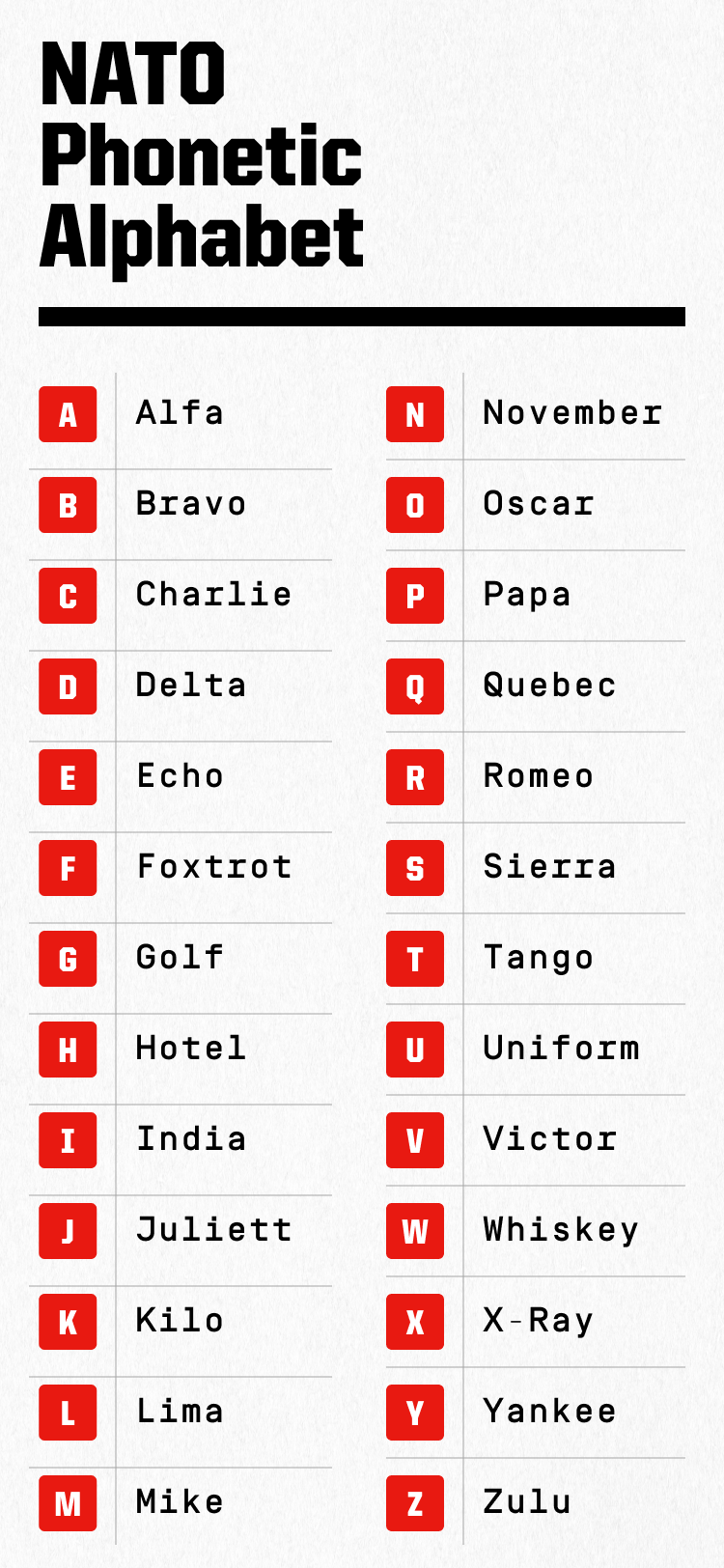

Once you pass the exam, your new license will last for ten years and you’ll also be issued a call sign using the following phonetic alphabet.

So the call sign W3TAB, for example, would be “whiskey-three-tango-alpha-bravo.”

These five-character names stand as a sort of license plate for your radio license that tells someone who is transmitting and where. This helps avoid confusion among common names (Dan, Mary, etc.) as each licensee is given a unique call sign. When exploring the sprawling ham radio community, whether on podcasts, YouTube, or elsewhere, you’ll often see experts prominently displaying their call signs as well as their names. To see who’s transmitting, operators around the world can go to QRZ.com and find out what call signs are attributed to which amateur radio operators.

“In the old CB days they called them handles, but this is something granted by the FCC that’s official,” Norman says. “So I use that call sign instead of my name when I’m on the air.”

What Kind of Gear Do I Need?

To broadcast over radio, you do need a few key ingredients. The two big ones are a transceiver which, as its portmanteau-ness suggests, can both transmit and receive radio signals. After that, you just need an antenna to catch those radio signals, and obviously a telegraph key.

Keys come in basically two flavors. There’s the straight key, which is what you see in World War II films when distressed sailors are sending out an SOS ( or ...---... if you were curious), and there are electronic paddles (both single and double) that automatically put in correct spacing and are all-around easier to use. Which one you go for is personal preference, and like anything else, prices can range from several hundred bucks to a fraction of that amount.

But if you’re agonizing over which telegraph key you want to try, Norman has a suggestion.

“There’s a school of thought that says you should learn using a straight key, so you learn to make the spacing, to make the dots, to make the dashes, and there’s another school of thought that says “oh forget that, that’s old fashion,” Norman says. “I like to teach Morse code by using the electronic keyer like a metronome… it just gives you that automatic spacing, then learn that spacing, that timing, that rhythm, then get over on your straight key and make it sound like what the other one sounded like.”

The combinations of keyers, transceivers, antennas, as well as other devices such as Radio Spectrum Processors (or RSPs) are endless, and you can check out ham radio stores, such as Ham Radio Outlet, DX Engineering, and Giga Parts, for gear and prices that make sense for your setup.

What Can I Do With Morse Code?

So after years of practice, taking a test or two, and investing several Benjamins into sending and receiving Morse code, what exactly can you do? Well, whatever you want, really.

“People say, ‘you know there are cell phones to communicate,’” Norman says. “That’s like asking someone in their sailboat, ‘you do know there are powered boats.’” The old-time novelty of Morse code is part of the appeal.

Just like with sailing, learning Morse code opens you up to a large, thriving, and passionate community of radio operators dedicated to practicing the art of dits and dahs. Entire podcasts and YouTube channels are dedicated to Morse code, and many CW clubs have developed a variety of awards and competitions for serious radio operators—and don’t forget to make the yearly pilgrimage to Hamvention outside Dayton, Ohio.

You can also join other Morse code radio operators in challenges like Summits on the Air (SOTA) and Parks on the Air, where people sent up mobile stations and transmit from mountaintops at state and national parks. Because Morse code is more condensed, it can be transmitted further on smaller radios, which is a necessity when counting every ounce in your backpack.

But maybe Morse code’s greatest gift is to inspire. It’s a kind of secret handshake among the Morse code initiated, and it also introduces people—young and old—to concepts of electronics, electromagnetism, and even meteorology. (The Earth’s ionosphere plays a big role in radio broadcasting.) And sometimes, learning ham radio and Morse code can even change your life.

“It got me into electrical engineering, and I worked on the Space Shuttle program for many years… It really launched my career,” Norman says, who worked on IBM’s in-flight computer for NASA’s Space Shuttle. “I would have never got to that point in my life had it not been for ham radio, electronics, and all the technical stuff I learned as a kid… next thing I know I’m working with astronauts.”

--. --- --- -.. / .-.. ..- -.-. -.-

(Good luck.)

..Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.